Have you ever been introduced to someone and promptly forgotten their name? Or have you ever worked with or seen someone enough socially that you ought to know their name? They know yours, and you’re no longer in a position that it’s socially acceptable for you to ask them theirs. You’re stuck, so now you’re sentenced to an indefinite period of either avoiding calling them by name, avoiding them altogether, or awkwardly trying to get someone else to say their name. Through little to no fault of your own, you’re going to be punished socially for an indefinite period of time.

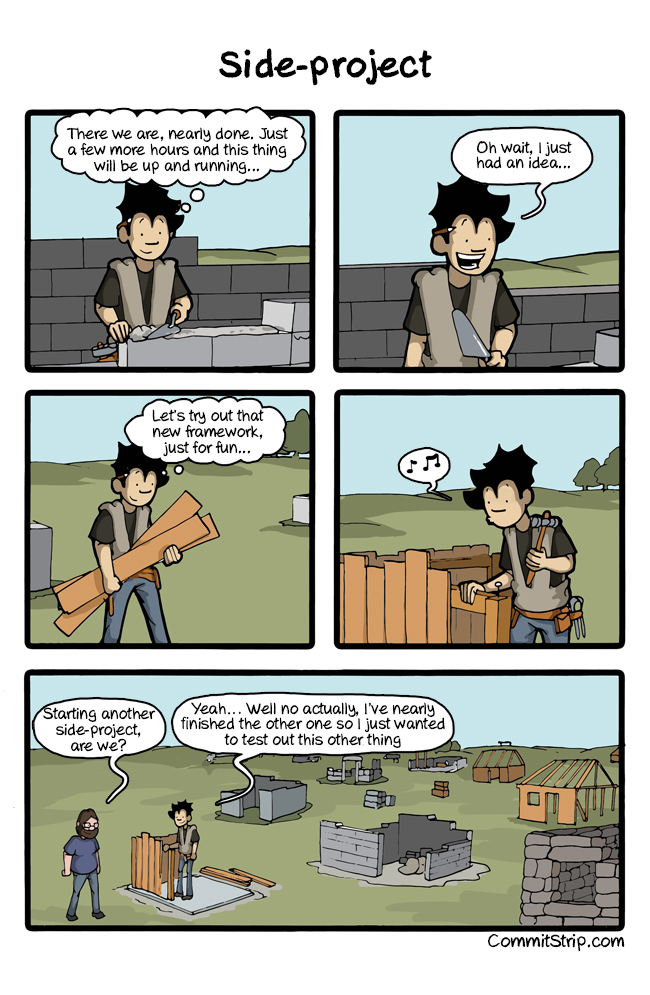

I think the feeling described strongly parallels the feeling that a developer has when the subject of unit testing comes up. Maybe it’s broached in an interview by the interviewer or interviewee. Perhaps it comes up when a new team member arrives or when you arrive as the new team member. Maybe it’s at a conference over drinks or at dinner. Someone asks what you do for unit testing, and you scramble to hide your dirty little secret–you don’t have the faintest idea how it works. I say that it’s a dirty little secret because, these days, it’s generally industry-settled case law that unit testing is what the big boys do, so you need either to be doing it or have a reason that you’re not. Unless you come up with an awesome lie.

The reasons for not doing it vary. “We’re trying to get into it.” “I used to do it, but it’s been a while.” “Oh, well, sometimes I do, but sometimes I don’t. It’s hard when you’re in the {insert industry here} industry.” “We have our own way of testing.” “We’re going to do that starting next month.” It’s kind of like when dentists ask if you’re flossing. But here’s the thing–like flossing, (almost) nobody really debates the merits of the practice. They just make excuses for not doing it.

I’m not here to be your dentist and scold you for not flossing. Instead, I’m here to be your buddy: the buddy with you at the party that knows you don’t know that guy’s name and is going to help you figure it out. I’m going to provide you with a survival guide to getting started with unit testing–the bare essentials. It is my hope that you’ll take this and get started following an excellent practice. But if you don’t, this will at least help you fake it a lot better at interviews, conferences, and other discussions.

(If you’re a grizzled unit-testing veteran this will be review for you, though you can feel free to read through and critique the finer points)

Let’s Get our Terminology Straight

One common pitfall for the unit-test-savvy faker is misuse of the term. Nothing is a faster giveaway that you’re faking it than saying that you unit test and proceeding to describe something you do that isn’t unit testing. This is akin to claiming to know the mystery person’s name and then getting it wrong. Those present may correct you or they may simply let you embarrass yourself thoroughly.

Unit testing is testing of units in your code base–specifically, the most granular units or the building blocks of your application. In theory, if you write massive, procedural constructs, the minimum unit of code could be a module. But in reality, the unit in question is a class or method. You can argue semantics about the nature of a unit, but this is what people who know what they’re talking about in the industry mean by unit test. It’s a test for a class and most likely a specific method on that class.

Here are some examples of things that are not unit tests and some good ways to spot fakers very quickly:

- Developer Testing. Compiling and running the application to see if it does what you want it to do is not unit testing. A lot of people, for some reason, refer to this as unit testing. You can now join the crowd of people laughing inwardly as they stridently get this wrong.

- Smoke/Quality Testing. Running an automated test that chugs through a laundry list of procedures involving large sections of your code base is not a unit test. This is the way the QA department does testing. Let them do their job and you stick to yours.

- Things that involve databases, files, web services, device drivers, or other things that are external to your code. These are called integration tests and they test a lot more than just your code. The fact that something is automated does not make it a unit test.

So what is a unit test? What actually happens? It’s so simple that you’ll think I’m kidding. And then you’ll think I’m an idiot. Really. It’s a mental leap to see the value of such an activity. Here it is:

[TestMethod, Owner("ebd"), TestCategory("Proven"), TestCategory("Unit")] public void Returns_False_For_1() { var finder = new PrimeFinder(); Assert.IsFalse(finder.IsPrime(1)); } I instantiate a class that finds primes, and then I check to make sure that IsPrime(1) returns false, since 1 is not a prime number. That’s it. I don’t connect to any databases or write any files. There are no debug logs or anything like that. I don’t even iterate through all of the numbers, 1 through 100, asserting the correct thing for each of them. Two lines of code and one simple check. I am testing the smallest unit of code that I can find–a method on the class yields X output for Y input. This is a unit test.

I told you that you might think it’s obtuse. I’ll get to why it’s obtuse like a fox later. For now, let’s just understand what it is so that at our dinner party we’re at least not blurting out the wrong name, unprovoked.

What is the Purpose of Unit Testing?

Unit testing is testing, and testing a system is an activity to ensure quality. Right? Well, not so fast. Testing is, at its core, experimentation. We’re just so used to the hypothesis being that our code will work and the test confirming that to be the case (or proving that it isn’t, resulting in changes until it does) that we equate testing with its outcome–quality assurance. And we generally think of this occurring at the module or system level.

Testing at the unit level is about running experiments on classes and methods and capturing those experiments and their results via code. In this fashion, a sort of “state of the class” is constructed via the unit test suite for each unit-tested class. The test suite documents the behavior of the system at a very granular level and, in doing so, provides valuable feedback as to whether or not the class’s behavior is changing when changes are made to the system.

So unit testing is part of quality assurance, but it isn’t itself quality assurance, per se. Rather, it’s a way of documenting and locking in the behavior of the finest-grained units of your code–classes–in isolation. By understanding exactly how all of the smallest units of your code behave, it is straightforward to assemble them predictably into larger and larger components and thus construct a well designed system.

Some Basic Best Practices and Definitions

So now that you understand what unit testing is and why people do it, let’s look a little bit at some basic definitions and generally accepted practices surrounding unit tests. These are the sort of things you’d be expected to know if you claimed unit-testing experience.

- Unit tests are just methods that are decorated with annotations (Java) or attributes (C#) to indicate to the unit test runner that they are unit tests. Each method is generally a test.

- A unit test runner is simply a program that executes compiled test code and provides feedback on the results.

- Tests will generally either pass or fail, but they might also be inconclusive or timeout, depending on the tooling that you use.

- Unit tests (usually) have “Assert” statements in them. These statements are the backbone of unit tests and are the mechanism by which results are rendered. For instance, if there is some method in your unit test library Assert.IsTrue(bool x) and you pass it a true variable, the test will pass. A false variable will cause the test to fail.

- The general anatomy of a unit test can be described using the mnemonic AAA, which stands for “Arrange, Act Assert.” What this means is that you start off the test by setting up the class instance in the state you want it (usually be instantiating it and then whatever else you want), executing your test, and then verifying that what happened is what you expected to happen.

- There should be one assertion per test method the vast majority of the time, not multiple assertions. And there should (almost) always be an assertion.

- Unit tests that do not assert will be considered passing, but they are also spurious since they don’t test anything. (There are exceptions to this, but that is an intermediate topic and in the early stages you’d be best served to pretend that there aren’t.)

- Unit tests are simple and localized. They should not involve multi-threading, file I/O, database connections, web services, etc. If you’re writing these things, you’re not writing unit tests but rather integration tests.

- Unit tests are fast. Your entire unit test suite should execute in seconds or quicker.

- Unit tests run in isolation, and the order in which they’re run should not matter at all. If test one has to run before test two, you’re not writing unit tests.

- Unit tests should not involve setting or depending on global application state such as public, static, stateful methods, singeltons, etc.

Lesson One Wrap-Up

I’m going to stop here and probably continue this as a series of posts. I’m going to be giving an “introduction to unit tests” talk, probably this week, so I’m doing double duty with blog posts and prepping for that talk. When finished, I’ll probably post the PowerPoint slides for anyone interested. Hopefully if you’ve been faking it all along with unit tests you can now at least fake it a little bit better by actually knowing what they are, how they work, why people write them, and how people use them. Perhaps together we can get you started adding some value by writing them, but at least for now this is a start.

It takes more time and energy trying to go around problems that it does trying to solve them.

![1916: 'PHYSICIST DAD' TURNS HIS ATTENTION TO GRAVITY, AND YOU WON'T BELIEVE WHAT HE FINDS. [PICS] [NSFW] 1916: 'PHYSICIST DAD' TURNS HIS ATTENTION TO GRAVITY, AND YOU WON'T BELIEVE WHAT HE FINDS. [PICS] [NSFW]](http://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/headlines.png)